Growing up in Milngavie, with its close proximity to the moors and the waterworks (now more formally recognised as Mugdock Country Park and Milngavie Reservoir), I was surrounded by landscapes that were deeply connected to my maternal grandmother’s family. Long before I began recording family history, places such as Barrachan were known landmarks rather than abstract names in old documents.

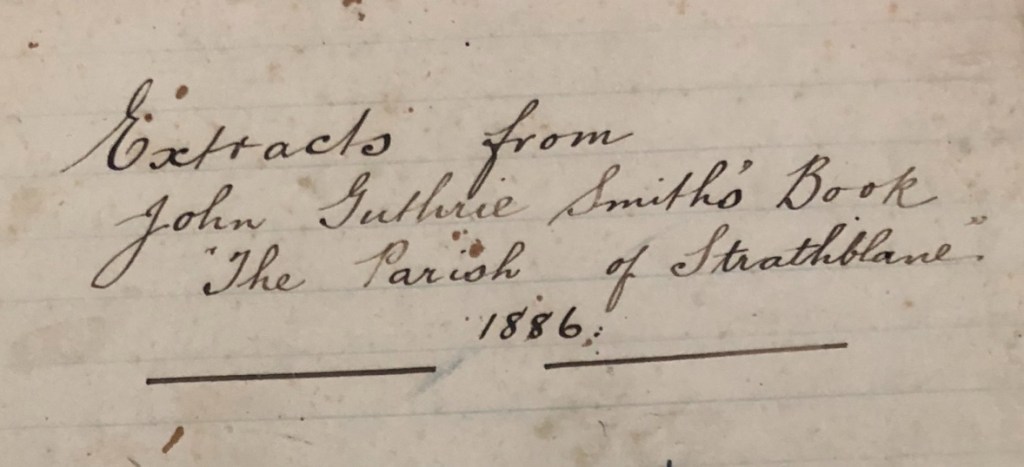

According to the book The Parish of Strathblane and its Inhabitants from Early Times by John Guthrie Smith, the Weirs had been present in the barony from “time immemorial”. Barrachan, in particular, emerges repeatedly in both family memory and historical sources, and has come to represent a focal point for understanding family dynamics and how the Weirs fitted into this landscape.

The house and lands of Barrachan are often referred to in family tradition as having been compulsorily purchased to allow for the construction of the reservoirs. This marked a clear and tangible end point to the Weirs’ long association with Barrachan and, although the family later spread to the four corners of the world, my mum, her mum and her grandmother all lived their lives within walking distance.

Tracing the Weirs themselves is rewarding and frustrating in equal measure. On the one hand, the designation “Weir of Barrachan” makes certain individuals relatively easy to identify. On the other, the strict adherence to Scottish naming conventions with repeated Jameses, Johns, Williams, Jeans and Elizabeths means that distinguishing between and even, within, generations is not always straightforward. Family annotations, including notes made by my great-grandmother correcting Guthrie Smith’s assumptions, are a reminder that even respected historical accounts are not infallible.

Guthrie Smith records that the Weirs were initially tenants of Barrachan, with heritable possession appearing to date from 27 April 1630, when Walter Ware obtained a feu charter for the lands. From that point onward, Barrachan largely descended from father to son — a strongly patriarchal pattern — with occasional complications, until the later nineteenth century, when the lands were taken from the family to facilitate reservoir construction.

From the evidence available, Barrachan appears to have functioned as a farmhouse within a working agricultural estate. It was associated with productive farmland, woodland and parkland, with houses, cottages and outbuildings forming part of a coherent estate landscape. Today, these elements survive — often fragmentarily — within the Milngavie Reservoirs, a Victorian engineered parkland recognised for its historic and scenic value. The buildings associated with Barrachan are included within the wider Category A listed Reservoirs site, and their contribution to the character and sense of place is acknowledged in Historic Environment Scotland’s Listed Building Assessment.

The condition of Barrachan Main House has been formally recognised through its inclusion on the Buildings at Risk Register. Nominated in 2019 by Friends of Milngavie Reservoirs, the building was assessed in 2022 as being in poor condition, with deterioration to roof detailing, rainwater goods and masonry, and with dense vegetation limiting full inspection. Although now secured, the building remains vacant and forms part of a wider complex of historic structures at Barrachan, all contributing to the character of the Milngavie Reservoirs Conservation Area.

Other information on Barrachan :

https://fomr.uk/ci-barrachan-house.html